Home | Programme | Abstracts | Colloquium | Find us | Contact us

Summaries by members of the doctoral colloquium, all photos below by JP de Ruiter.

- Wednesday

- Thursday

Wednesday

Session 1: 09:30-10:55

Staffan Larsson: Grounding as a Side-effect of Grounding

Summary by Shauna Concannon

Steffan Larsson’s talk sought to connect communicative grounding, and in particular semantic co-ordination, with a formal model of perception and meaning based on symbolic grounding. Faced with the challenge of integrating perceptual meanings and low-level perceptual data into formal semantics, they were attempting to address the problem using a Type Theory with Records (TTR) perceptron classifier.

The talk detailed efforts to develop a formal model of perception and meaning based on symbolic grounding. Symbol grounding is the process by which we connect symbols to the world, in such a way that supports composition and learning.

Through the process of semantic co-ordination we attempt to establish the meanings of linguistic expression in interaction. This is achieved through a number of mechanisms such as corrective feedback, implicit and explicit word meaning negotiation and litigation, etc. Clarification requests and feedback allow us to communicate to an interlocutor that their interpretation is aligned with our own. This iterative process of semantic co-ordination is an integral aspect of communicative grounding, but, as Larsson suggests, can also lead to symbolic grounding.

As such, the development of a formal semantics using TTR, which aims to account for the connection between communicative grounding and symbolic grounding was undertaken. In interaction, symbolic grounding can result from communicative grounding of concrete referring expressions in a shared visual environment. However, developing a computational cognitive model that solves the binding problem of symbolic and non-symbolic representations in the brain is no mean feat.

Artificial Neural Networks are a form of connectionist model in which data is classified through a parallel computational process. Due to the distributed nature of processing, it has been argued that symbolic understanding cannot be directly constructed within connectionist networks and that the two models are diametrically opposed. The challenge of instantiating the sources of power of symbolic computation within a fully connectionist system has been the concerns of many leading cognitive scientists, with many adopting various hybrid approaches.

He described a study they had conducted using a TTR perceptron classifier to identify left from right and act as a proof of concept for the system.

Chris Cummins: Getting implicatures wrong

Summary by Shauna Concannon

Chris Cummins’ talk explored how, when and why we get quantity implicatures wrong. He suggests that the domain of numbers is an interesting context for investigating implicature.

Although we are very adept at recovering a speaker’s intended meaning, we are also strongly disposed to infer context when we interpret sentences; this can lead to potential misunderstandings that may never be recovered through the course of interaction. As such, interlocutors can maintain differences in their interpretations as a consequence of our disposition to infer meaning.

Starting with the example of the choice of ‘some’ as a quantifier, it was demonstrated that a typical inference from the statement ‘I saw some of your children at the park’ would be ‘I saw some but not all not all of your children at the park’.

The hearer reconstructs the speaker’s intention to convey that they did not see `all’ simply from the choice of quantifier ‘some’. Indeed we seem to be very good at reconstructing this intention, however, the gap between intended and actual can sometimes be significant. Once we progress to more numerical quantity implicatures the situation become a little more complex.

People tend to attribute very specific understanding to terms such as ‘less than 100’ and ‘more than 80′. What a speaker intends when issuing such a term may not be evident; furthermore, whether they themselves have clarity over the meaning of the selected term is not a given.

However, if hearers do infer the relevance or significance of the number selected then this could lead to misalignment. It may be quite difficult to detect when such a misalignment has occurred and in some instances this could lead to further consequences. The example provided, gave a case of a doctor informing a patient that the chances of side-effects when taking a new drug were `less than 5%’. The doctor’s intended meaning was 1-5%, however if a patient infers 4-5%, it may lead them to choose against taking the medication.

In order to explore the variability of interpretation in the domain of numbers, an experiment was conducted using fragments featuring quantity implicatures from the British National Corpus. Responses to four questions about the examples of quantity implicature were collected on a five point likert scale, using Mechanical Turk. The questions were presented as follows:

Example from BNC: `more than 60′

1. In the speaker’s opinion, the actual number of [X] is less than 80

2. The speaker said “more than 60” because that was the most informative statement possible.

3. The speaker said “more than 60” because that was a convenient approximation.

4. The speaker said “more than 60” because the specific number 60 was important for some reason.

A strong negative correlation was found between Q1 and Q4; the perceived relevance of the number suppresses the implicature and the lower the number given, the more significant the respondent thought the number was. The pilot data seemed to support the idea that hearers are very adept at recovering speakers’ intended meanings, but are strongly disposed to infer contexts when interpreting sentences in fragment form. In real situations we are interacting with a real speaker with actual intentions and thus have access to a great deal more context.

In the discussion that followed whether the resulting phenomenon of such interactions is indeed miscommunication or merely a disparity, disinformation or anti-communication was called into question. It was offered in response that the line between miscommunication and communication is not categorical, and fittingly the various understandings of `miscommunication’ within the room traversed a spectrum. The case of quantity implicatures highlighted this issue particularly well.

Session 2: 11:30-12:30

JP de Ruiter: Modelling miscommunication

Summary by Pollie Barden and Giulio Dulcinati

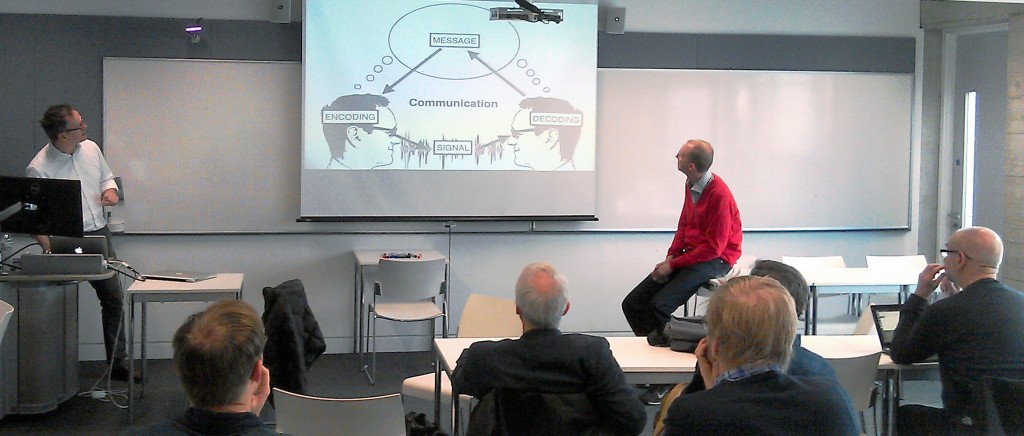

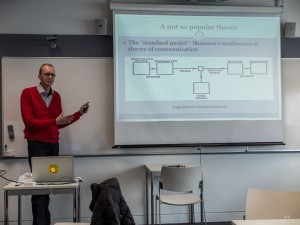

JP de Ruiter’s talk explored how the conduit metaphor of communication as based on a message may be more useful than an holistic view of communication as based on intentions if the goal is to construct a model of communication that will enable artificial agents to interact.

Shannon’s mathematical theory or conduit metaphor of communication as involving a speaker encoding a message and sending it to a receiver for decoding has been criticized and abandoned by many theorists. The critiques are that (i) communication is holistic (i.e. jointly constructed by interlocutors) and it is not possible to separate sender and receiver, (ii) communication is not about the message but about the intentions of the interlocutors.

However, the conduit metaphor should not be dismissed because it is useful for constructing a model of communication that can be implemented. It is demonstrated well in text messaging systems with explicit sender and receiver. So we should ask what a linguistic unit encodes in the complex “natural” language. A possible answer is the following. A linguistic unit (e.g. I hate eating porridge) encodes a communicative intention (e.g. a complaint), a predicate (hate[I, eat[porridge]]) and arguments (I, porridge). These three types of information are also the sources for miscommunication. Transmission of the communicative intention can lead to misunderstanding of the social action being carried out. The grammatical structure is responsible for syntactic ambiguity and the arguments are the source of ambiguity in reference.

In conclusion, JP proposed why he was pursuing this line of investigation. The computational nature of conduit facilitates implementing an interface with BDI engines (robots). The limited affordances of the robots provide a means for different modeling of miscommunication between artificial systems.

In the discussion session the following questions were raised:

Q: Did Aston ever use the word intuition?

JP – Social action is always misunderstood. Illocution is too difficult to remember for students.

Conjunction – I object to the idea that the messages are encoded and send along channel and decoded at the other end. The distinction is between decoding and conjunction.

Q: What is good about the conduit metaphor?

JP – It is a practical metaphor and it explains things. The idea of a message passing from sender and receiver makes it clear for programming. It is how normal people conceptualize the process.

Q: Some object to the idea that communication is ‘encode, transmit, decode’ – and that is the end of the story.

JP – I agree. We exchange a few bits but lose most of the information. We can make inferences. Shannon is not enough to make all the machinery work. However, if we talk like Redding then we would not be able to communicate in the “enthos” or real sense.

Robin Cooper: Dynamic linguistic resources: a recipe for miscommunication

Summary by Pollie Barden and Giulio Dulcinati

Robin Cooper’s talk focused on the observation that language seems to gives its users infinite opportunities to miscommunicate. In the talk, Cooper explored four main aspects in which languages seem to be ever-changing and dependent on the situation rather than fixed ‘reliable’ systems.

The first aspect is related to the fact that interlocutors create ‘micro-languages’ for the purposes of a particular situation. In this sense the view from 20th century linguistic semantics that natural languages are formal languages does not seem tenable. Rather, languages seem to be ‘toolboxes’ that only give speakers the resources to construct local languages to be used in specific situations.

The second aspect is related to the fact that the meaning of words seems to be created on the fly. Words do not have a fixed meaning (or set of meanings). Rather their meaning space in use seems to only have the limits of what the hearer can recover.

A third aspect is related to the fact that direct quotations of speakers’ utterances seem to vary in how similar they are to the original. There is no standard degree of quotational similarity across situations. Rather, hearers have to recover the aspect of the quotation that is presented as imitative.

A fourth and final aspect of change is represented by reasoning patterns. The arguments that speakers use in communication do not form a unified and consistent system across conversations. Rather they vary from situation to situation.

The leitmotif of the talk was the observation that although these ingredients seem to make up a recipe for disaster, we manage to communicate anyway. And Cooper pointed out that this observation raises the question of whether our speciality is recovering what the speakers intend to communicate or ignoring all the miscommunication that our ever-changing languages are bound to cause.

Session 3: 13:30-14:25

Matt Purver: Miscommunicating with computers

Matt presented a joint project with (amongst others) Julian Hough and Christine Howes exploring some of the ways that dialogue systems can begin to deal with complexities of natural language such as repair phenomena.

The presentation began with a demonstration of data from some more traditional ASR (Automatic Speech Recognition) approaches to disfluencies and repair – which typically follow a clarification and confirmation paradigm, which can lead to low confidence in unconstrained application domains and amusing/time-consuming miscommunications. Because repair is incremental, Matt showed that models of self repair (particularly) needed to take this into account in detecting and then dealing with this in speech recognition.

He then showed some empirical work on naturalistic doctor-patient communication focussing on using automated language processing on transcribed recordings of psychiatric interviews. In these contexts, they were able to show that automated analysis of self and other-repair phenomena could be extracted and associated with measurable effects on diagnosis of symptoms and prediction of outcomes.

The presentation concluded that standard computational models of repair were insufficient, but that a reasonable approximation of self and other-repair could be developed using low level features. The challenge for the future would be to move to the higher level semantics, pragmatics, and phonology involved in these mechanisms.

Herbert H. Clark: Cost-benefit Analyses in Communicating

Summary by Ioana M. Dalca

Cost-benefit analyses of effort may describe communication. In addition to minimising individual costs, members of a communicative act prefer to minimise their joint costs (e.g. through repair, face saving, devices of subterfuge, etc), in part by minimising collective costs (e.g. via conventions) over respective benefits. Such balancing processes may also be mirrored in animal behaviours with controlled costs such as efforts that are employed in reaching a fixed goal (or benefit).

Similarly, the compromise between speaker and auditor economy brought forth in Zipf’s law of abbreviation (1949) comes from the process of grounding. In the tangram task by Clark & Wilkes-Gibbs (1986), grounding is exemplified by matchers’ and directors’ expansion and contraction of utterances (through follow-up or completion) in order to indicate whether longer or shorter references are necessary; the tendency for shortening references over trials may also be seen as directors’ preference for minimising joint effort. This reduction of effort is also reflected in the tendency to point, instead of speak, when the circumstances of the interaction allow it. At two ends of a table, directors and builders of Lego objects are more efficient when the workspace is visible, in terms of the total time and word number employed by each member (Clark & Krych, 2004).

The resources that are available to each member and their physical abilities lead them to redistribute individual effort in various ways in order to minimise joint costs. In a computer version of the tangram task, Gumbrecht and Clark (in preparation) allowed the directors and matchers to communicate either by speaking or by typing. These two modalities exhibit a difference in production effort, the latter being more time-consuming for equivalent understanding. Speaker-speaker pairs were about 3 times faster than typist-typist pairs; in diads with unequal partners, speakers were observed to assume a role that enabled typists to type less, as evidenced in the number of management and content questions. In general typists used textese to minimise effort, through omissions of unnecessary words, hedges and disfluencies, use of abbreviations, acronyms & symbols, lower case text and ignored misspellings.

Questions revolved around the ways in which we can elucidate whether joint effort is different from the sum of individual costs, the differences between joint and collective effort and the ways in which effort can be measured in multimodal communication. Franklin’s principle is relevant here: time is money.

Thursday

Session 1: 09:30-10:55

Paul Drew : On failure to understand what the other is saying

Summary by Sam Duffy and Jemima Dooley

Paul worked with Claire Penn from South Africa on this conversation analytic (CA) study of an extreme example of miscommunication between an elderly woman with aphasia (JD) and her speech therapist (R). JD is talking about something important to her from her past that she wants R to understand. However R repeatedly claims not to understand JD’s multiple attempts. Detailed analysis of this situation suggests a solution for what JD is saying, and several ways in which both JD and R attempt to achieve congruence on it.

Firstly, this example of a misunderstanding was not just evidenced by analysts examining the data subsequently. The lack of mutual comprehension was recognized by both participants at the time (R’s: “I’m not getting this”, occasioning repeats and ongoing pursuit of uptake by JD). So what is causing R not to understand what JD is saying? A range of difficulties in the consultation were raised:

- mistaken referent (Schegloff): R thinks that JD is talking about her boyfriend at the time when in fact she is talking about herself.

- Mismatch: At one point, after multiple repeats of a ‘laughable’ matter, JD laughs immediately after her turn, but – without an explicit demonstration of lack of understanding – the therapist can only smile responsively.

Here Paul referred to Bar-Hillel’s – work on descriptive language: that descriptions are always ‘done’ for a purpose. For example, a written methodology for an experiment is on the surface dry, neutral and technical, however the purpose is to persuade the reader of the credentials of the authors’ experimental rigour. So in this session Paul asked: what is JD trying to do by describing “BA” and (as the transcript renders her unintelligible phrase) “the skanner girl”?

Paul quotes Goffman who writes that the speaker’s task is to design talk to be understood by the other in the way that you wish it to be understood. Analysis of this fragment reveals something important: the stress on the word “and” in ‘BA and skanner girl’ suggests the word is used compositionally, it comes formulates something greater than its parts. Here JD is saying she has a BA AND was working as a mechanic (a ‘spanner girl’). The ‘and’ refers to the contradiction here, incongruence of the role she had at the time as a female mechanic (skanner girl) with a higher education (BA). It is this that the therapist does not understand.

There are many dimensions of language and interaction, including turn taking, epistemics, grounding and space. These each give partial accounts, no single one can claim to capture everything about an interaction. Paul suggests congruence (or incongruence) as an addition to this list might best explain the interaction – or miscommunication analysed in his talk.

Adrian Bangerter: Correlates and effects of delayed responses to job interview questions

Summary by Sam Duffy and Jemima Dooley

In the job interview situation, impression management is incredibly important. The Past Behavior interviewing technique (for example “tell me about a time when you failed to deliver a project on time, and what you would now do differently to achieve a different outcome”) requires candidates to both search their memory for a suitable example and then construct a logical and compelling narrative. Respondents may sometimes be unclear as to whether a story is expected, rather than a short precise answer. Listeners (here the hiring manager) commonly use disfluencies (‘um’s, pauses) to quantify the respondent’s competence in answering the question. There is a trade off between the time required to search your brain for an appropriate answer and risk looking inept, or a quick response without a properly formulated or appropriate answer. An extreme example in the data showed a 23 second pause, after clarification question.

Adrian’s work aims to answer the question ‘Do long pauses in job interviews affect hireability?’ The team have developed a taxonomy of response patterns from analysis of 62 real research job interviews. The responses were coded for type of response, narrative vs non-narrative with a specific focus on the preceding pause length. It was found that as time goes by, candidates were increasingly likely to give up on narrative responses. Longer pauses predicted non-narrative responses. So does the delay lead the candidate to abandon the search for a suitable narrative answer? Would they have found a suitable narrative eventually or did they simply recognise that they could not formulate one or didn’t have a good enough example? To take this further, can we predict hiring decisions from the pause lengths? Adrian reported that even taking out the effect of gender and test scores, increased pause duration reduced the likelihood of being hired. This was described as a small but significant effect.

Questions after the talk included;

- Did you look at just gaps? Were any other measures looked at?

- How do you know that the timing is significant? Correlation to quality of the answer?

- The longer pause could give you the chance to get a better answer.

- Does an immediate answer have a negative effect (implies no thought at all), or just evidence of good preparation?

- How can we measure answer quality? – Relevance? Impressiveness? Or is the fact the person is hired a measure of quality?

- Is there a linear relationship? I.e. shorter pauses mean more likely to be hired, but does this continue to mean no pauses, or even overlaps, would mean it is even more likely you are hired?

Rose McCabe: Miscommunication in doctor-patient communication: Is getting it wrong, getting it right?

Summary by Sam Duffy and Jemima Dooley

Rose posed some questions specific to communication in medical context:

- What do we consider as effective communication in a medical context?

- Do we specify this as communication that is good enough for the current purposes, e.g. patients agreeing to take their medication in the clinic, or to longer-term ends, e.g. patients continuing to take their medication over the course of their illness?

- This may be dependent on the goal of the medical consultation, but who defines this – the patient or the doctor?

There are clear placebo effects resulting from patient-consultant interaction in medical settings. What is the therapeutic effect that we can see the results of, but which is not related to direct intervention such as surgery or drugs? This is especially important in psychiatric interviews, where patients are diagnosed and treated primarily using communication methods.

Psychiatrists use outpatient interviews with patients who have ongoing illnesses to review their mental state, medication and social functioning. Schizophrenia has a high non-adherence rate to medication – so patient satisfaction and adherence to treatment is especially important. Lapses in adherence can have serious implications. So, how best to keep the patient engaged to complete their treatment?

Previous research has shown that patients often try to talk to the psychiatrist about their illness, to try and make them understand their experiences. However psychiatrists sometimes avoid discussion of the details of their symptoms to focus on the task at hand, which leads to low patient satisfaction. The theoretical model explored here is that shared understanding in consultations will be linked to better patient outcomes.

Doctor self-repair, and repair initiators by patients, were measured as an indices of effort in formulating understanding and recipient design. From this we see that;

- Patient led clarifications were associated with adherence to medication.

- Doctor self-repair was associated with patient self-reported ratings of satisfaction.

It came as a surprise that patient led clarification was a predictor of adherence to medication*, as initially it was thought that the driver would be the consultant’s communication. However analysis revealed that patient NTRI occurred when they felt that a question had already been answered satisfactorily, but the consultant was still pursuing it, or when the consultant made an unmarked topic shift. The team were not expecting miscommunication of this sort in consultations to have a positive outcome.

As a follow up study, a group of doctors were given training in consultation communication, and compared both pre- and post- training with a group of untrained doctors. Self repair, which had been linked to patient satisfaction (and was a possible indicator of the doctor being more engaged), did not go up. However it went down in the untrained group. Patient rating of their consultation did improve with doctor training. However, patient satisfaction was not directly associated with adherence.

*It is important to note that there is the question of whether patients who are more adherent are more likely to be involved in their communication anyway.

Session 2: 11:30-12:30

Jenny Roche: (Mis)communication, ambiguous lexical choices, and perspective taking in dyadic tasks

Summary by Diana Mazzarella and Giulio Dulcinati

Jennifer Roche’s talk explored the relationship between miscommunication and perspective-taking, that is, the ability to track the perspective of our interlocutors when this does not match our own.

The talk focused on lexical choices in a natural task based dialogue exchange (‘Bloco corpus’). The data presented showed that communication and miscommunication are predicted by different lexical choices: while grounding (‘Ok, got it’), assent (‘yup’) and personal pronouns correlate with success in communication, negation (‘nope’) and spatial expressions (‘Up’) are predictors of miscommunication. Interestingly, the interpretation of spatial expressions requires the addressee to adopt the spatial perspective of the speaker. As a consequence, failure in perspective-taking may result in miscommunication.

Furthermore, Roche presented interesting data about the trajectory of miscommunication. High and mean accuracy in the performance of the task seem to correlate with fluctuation between successful and unsuccessful communicative exchanges in the course of the task. These results crucially highlight the multi-faceted valence of miscommunication. Rather than excluding miscommunication, successful communicative exchanges rely on the transition between local success and local failure. This transition could be seen as promoting a system of checks and balances, with a beneficial impact on the overall performance in the dialogue exchange.

Early miscommunication can promote, rather than undermine, coordination between interlocutors and facilitate the emergence of efficient referential conventions. (Note that an interesting parallelism can be drawn here with Gregory Mills’ data on referential coordination in dialogue, where we find that early disruption can promote semantic coordination).

Gregory Mills: Semantic coordination in dialogue: miscommunication drives abstraction

Summary by Diana Mazzarella and Giulio Dulcinati

Gregory Mills’ talk started from the consistent finding in interaction research that interlocutors start with long and cumbersome ways of referring and during dialogue they develop a shortened, abstract and efficient referential system. Interestingly, while referential conventions that rely on physically salient features require low coordination, the development of abstract referential systems seems to require a high degree of coordination of the participants.

This association between coordination and the development of abstract referential systems leads to the question of what happens to the referential systems when coordination is disrupted. Mills showed data from an experiment where pairs of participants had to give each other instructions through a chat in order to solve a series of mazes and coordinate on giving spatial reference to navigate each maze. The experiment had a control condition in which participants solved all the mazes without being disrupted, and two experimental conditions. In one experimental condition the participants were disrupted during the first half of the experiment and in the other experimental condition they were disrupted during the second half of the experiment. The disruption consisted in the injection of artificial clarification questions in the dialogue. The clarification questions were presented to one participant as if they came from the other participant, while the other participant was unaware of both the clarification question and clarification answer appearing in the dialogue. Several variables were measured, among which ‘semantic coordination’ (i.e. degree to which pairs used the same words).

Surprisingly, results showed that pairs who were disrupted in the first half outperformed both control pairs and pairs disrupted in the second half of the experiment. On the other hand, late disruption was found to be detrimental to the task performance, as expected. Mills suggested that the results might be explained along the following lines: early disruption led participants to work harder for coordination, which in turn led to increased semantic coordination. Late disruption breaks ‘conceptual’ or ‘semantic pacts’ between participants, and consequently decreases their confidence in the task.

Session 3: 13:30-14:25: Summarised by Johanne Stege Bjørndahl and Nicola Plant

Mark Dingemanse: A cross linguistic study of other-initiated repair

Summary by Johanne Stege Bjørndahl

In his talk, Mark Dingemanse reported from a large study looking at other-initiated repair sequences in occurrences of natural speech from 31 languages. Dingemanse and colleagues analyzed the data using a combination of qualitative methods (CA), coding, and statistical modeling (mixed effects models). The study found that in particular one open class repair initiator looked surprisingly similar across the 31 researched languages, suggesting a universal repair initiator: “huh?” consisting of a low frontal vowel and a questioning intonation. In the following discussion the question was raised whether the many different “huh?” – like repair initiators across languages were mainly produced with a rising intonation. Dingemanse specified that this particle was indeed produced with rising intonation in most cases, but in some languages where questions are generally produced with falling intonation subsequently the repair initiator show falling intonation, hence the somewhat ambiguous usage of the phrase “questioning intonation”.

Dingemanse went on to discuss findings relating to different classes of repair initiators, open repair initiators such as “huh?” compared to restricted repair initiators such as confirmations (“she did?”) and clarifications (“who did?”). Dingemanse presented results from a range of different languages showing that they all have repair initiators that fall into these three different types: open/restricted, confirmations and clarifications, however with different distributions in usage. This analysis relies on data and work by Kendrick, Blythe and Levinson among others. Along the lines of these findings, Dingemanse reported from qualitative analysis of repair sequences showing that people engaged in dialogue generally opt for the lowest joint cost solution when doing repair. When possible, addressees tended to go for restricted repair initiators, because it reflects a lower shared cost than open class repair initiators.

Open class initiators were found mostly when the repair was processing related i.e. occurred as a response to problems with the message being audible, attended to, and/or readily anticipatable.

Dingemanse ended his talk with a quotation from Chomsky: “a Martian scientist might reasonably conclude that there is a single human language, with differences only at the margin”. Dingemanse, however, put his own spin on it: looking at universality not as evidence of an underlying structural or grammatical rule based system governing linguistic capabilities, but rather as a multiplicity of expressions following from a set of similar resources fit in diverse ways to similar needs.

Pat Healey: The Body’s Natural Defences Against Communicative Disease

Summary by Nicola Plant

This presentation looked at the role of embodied interaction in dialogue with a particular interest in miscommunication. This reports on a research project by Plant, Healey, Lavelle, Frauenberger, and McCabe asked why do we gesture and nod in conversation? One hypothesis is that it aids speech production, or perhaps we do it because we see others doing it.

Various theories have emerged on this theme, such as the hand-in-hand hypothesis and the trade-off hypothesis (de Ruiter, Bangerter, Dings 2012). However, the research presented suggested that gesture is very closely connected with miscommunication within interaction. The study looked at a corpus of dyadic interactions, where interlocutors were given a storytelling task and so were asked to talk about a recalled bodily experience, such as a headache or yawning. In order to test the hypothesis that gesture is linked with miscommunication, the study looked at occurrences of clarification questions and repair in the corpus.

Observations from this study showed firstly that storytelling is an asymmetric task; narrators say a lot more and gesture a lot more, listeners tend not to gesture when the narrator is talking. However, both narrator and listener gesture a lot more during instances of clarification and repair compared to when they are just telling the story. The listener in particular gestures much more actively when asking a clarification question than usual. For self-repairs, both actively gesture. The conclusion thus far is that gesture is very closely connected with clarification and repair. When dealing with miscommunication, the task is inherently collaborative; both narrators and listeners enlist more non-verbal resources than usual to resolve the problem.

Discussions

Home | Programme | Abstracts | Colloquium | Find us | Contact us